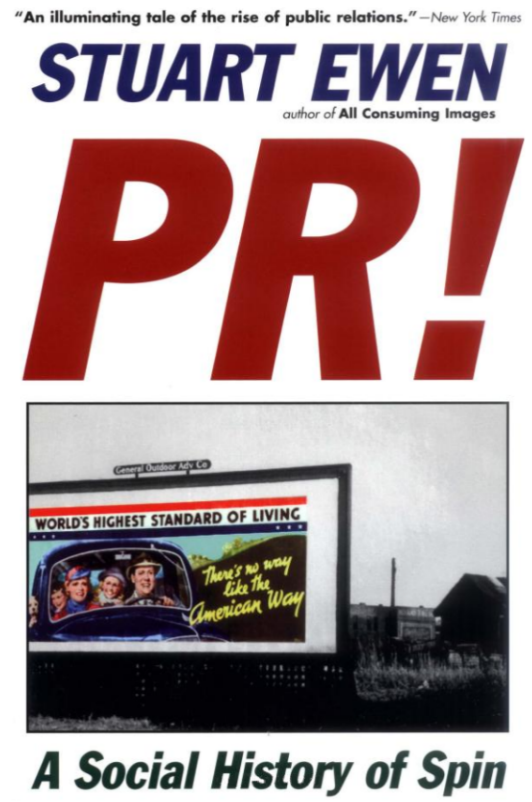

Ewen, S. (1996). PR: A social history of spin. New York: Basic Books.

Stuart Ewen’s PR: A Social History of Spin (1996) is a critical and illuminating exploration of the history and cultural significance of public relations (PR) as a tool of power, persuasion, and social control in the modern world. Written with the precision of a historian and the insight of a cultural critic, Ewen traces the origins of public relations not merely as a business strategy but as a response to crises in legitimacy faced by elites in the age of democracy, mass media, and consumer culture. The book is not just a chronology of events but an intellectual history of how modern public consciousness has been shaped — and often manipulated — by those seeking to manage perception, shape behavior, and manufacture consent.

Ewen’s central argument is that the emergence of public relations in the early 20th century was not an accidental development of the advertising industry, but a deliberate response to growing popular pressures for social equality, democracy, and accountability. In an age when industrial capitalism was creating immense social inequalities, public dissent, labor uprisings, and demands for greater participation in political life, elites — corporate leaders, politicians, and social institutions — turned to PR to "manage" public opinion and protect their interests.

The historical narrative begins with the industrialists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the United States, who faced growing hostility from workers, reformers, and journalists. Figures like Ivy Lee and Edward Bernays emerge as foundational architects of modern PR. Lee introduced the idea of "public information" to counter negative press about monopolistic corporations, framing corporate interests as benevolent and essential to national progress. Bernays, influenced by his uncle Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theories, pioneered techniques of subconscious persuasion, branding PR as the "engineering of consent." His campaigns, which ranged from promoting cigarette smoking among women to political propaganda, revealed how deeply PR was embedded in the construction of modern identity and consumer behavior.

Ewen situates PR within the broader currents of social and intellectual history. The early 20th century was not only a time of industrial upheaval but also of technological transformation — the rise of radio, cinema, and later television created unprecedented avenues for reaching the masses. PR practitioners recognized that in the emerging mass society, where individuals were increasingly isolated and information flows centralized, the manipulation of symbols, emotions, and images became a crucial form of power.

One of the book’s most striking contributions is its analysis of how PR became central to the production of "reality" in modern democracies. Ewen shows that beyond selling products, PR has functioned to sell ideologies, political programs, and social norms. He examines how corporations and governments alike crafted "public images" not merely to inform, but to neutralize dissent, discredit opposition, and manufacture trust in systems that often operated against public interests. This analysis is especially relevant in Ewen’s discussion of Cold War propaganda, where PR methods were harnessed to present the capitalist West as a world of freedom and opportunity, masking both internal inequalities and external imperial ventures.

Furthermore, Ewen interrogates the ethical and philosophical implications of a world mediated by PR. He challenges the assumption that the public sphere is a domain of free and rational discourse, suggesting instead that it has often been colonized by engineered messages designed to evoke emotion rather than critical thought. This raises disturbing questions about the health of democratic societies, where participation may be reduced to passive consumption of carefully curated narratives rather than active, informed engagement.

Ewen’s critique does not simply demonize PR practitioners; rather, he situates them within the structural imperatives of capitalist modernity, where image management becomes a survival strategy for institutions facing democratic demands. PR is presented as a symptom of deeper contradictions — between democracy and capitalism, between public welfare and private power, between truth and spectacle.

In conclusion, PR: A Social History of Spin is a landmark work in the sociology of communication and cultural studies. It offers a rich, layered understanding of how public relations has evolved into a pervasive force shaping modern life. Ewen’s analysis remains profoundly relevant in today’s media-saturated environment, where social media, branding, influencer culture, and corporate activism continue to blur the boundaries between authenticity and manipulation. His work is a critical reminder that in societies where image often eclipses substance, the struggle for truth and democratic participation requires not only skepticism but historical awareness of the forces that have shaped our collective consciousness.